Just outside the city of Greifswald, on the German Baltic coast, stand the ruins of the Eldena Abbey. Construction began in the early 13th century and was completed by 1500. In 1535, however, the Abbey was dissolved and over the centuries fell into dereliction. Eldena has been a ruin then for far longer than it was ever operational, and in the early decades of the 19th century, became a key inspiration for the painter Caspar David Friedrich, whose images of the ruin helped cement its place in the German cultural imagination; a place it holds to this day.

What is it about ruins that fascinate us? Undoubtedly there is some aesthetic quality to be found in a crumbling building, something which has inspired many explorers, artists and other wanderers over the years, from Friedrich picking his way through the grounds of Eldena to the 21st century Urbexer, climbing through a broken window to capture high-resolution images of abandoned swimming pools, factories and cinemas.

Ruins also give us a link to the past, helping explain the stories that got us from there to here; the changes in politics, religion, society and culture in general. What led this building to be built? What led this building to be abandoned? What does it mean today? All these questions, that hover above the peeling walls and collapsed roofs of ruins, can help us tell the story of a place.

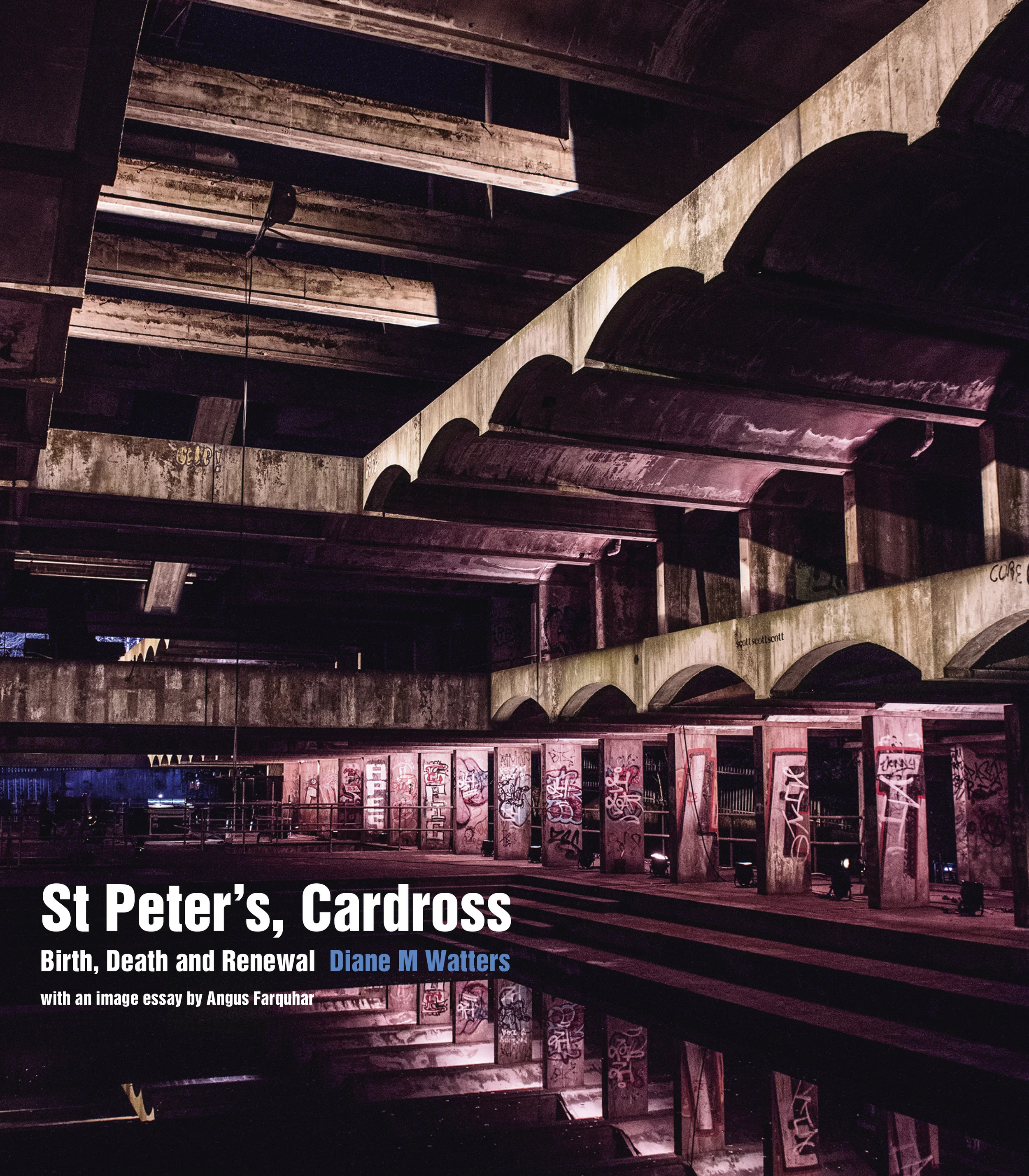

The ruins of St Peter’s College has stood on a hill above the village of Cardross in Scotland for over thirty years. Built as a seminary, St Peter’s fulfilled its original role for a mere fourteen years, from 1966 to 1979. From the beginning, the design of the building made it difficult and expensive to maintain. It was a striking example of Modernist architecture, one that would be simultaneously lauded as one of Scotland’s finest 20th century buildings and derided as one of its worst, and from the most of its abandonment developed “a mythical, cult-like status among architects, preservationists and artists.”

Today, fifty years after it opened its doors, St Peter’s College is in the process of a renovation that will allow its renewal as a cultural space, to be ready sometime in 2019. To celebrate the anniversary of St Peter’s, and to reflect on its history and its story, the architectural historian Diane M Waters has traced this story of an architectural failure which morphed into a tragic, modernist myth in St Peter’s, Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal. Within the pages of the book, published by Historic Environment Scotland, is also an image essay by Angus Farquhar which tells the story of Hinterland, an event that was intended to re-introduce St Peter’s as a place of creativity and inspiration.

With plenty of images and illustrations to help tell the story, St Peter’s, Cardross is a fascinating look at the history of a building, and how the dynamics of the world around it have shaped its story, both as a seminary and, later, as a ruin that inspired generations of artists and dreamers. Farquhar writes, close to the end of the book, of the cleanup process at the site:

I was worried whether the site clearance would ‘ruin the ruin’. What if the powerfully desolate character which had attracted so many people to visit and make work there over the last two decades was erased? What if, in becoming safe, it would also become bland? But week by week the original lines of the building were rerevealed, showing the experimental and sculptural qualities of the design to startling effect. As it was cleared of debris a new clarity and lightness pervaded the different spaces.

In Eldena, just outside Greifswald, the University of Greifswald hold concerts, theatre performances among the ruins of the Abbey during the warmer months of the year. As well as inspiring buddy artists and photographers, who wander through the red brick ruins, it has become a place of continuing art and culture; it may have been built as an abbey, but its legacy is centuries of artistic and creative inspiration. St Peter’s, standing above Cardross, is another “beautiful ruin” of a very different time and place, but one which looks as if will become an inspiration for years to come.

SPECIAL CHRISTMAS OFFER: buy St Peter’s, Cardross now for £20 (RRP £30) with free UK P&P using the code STPETERS20. (Offer valid until 20 December 2016). Buy online here.