Everything I Didn't Find in Vancouver

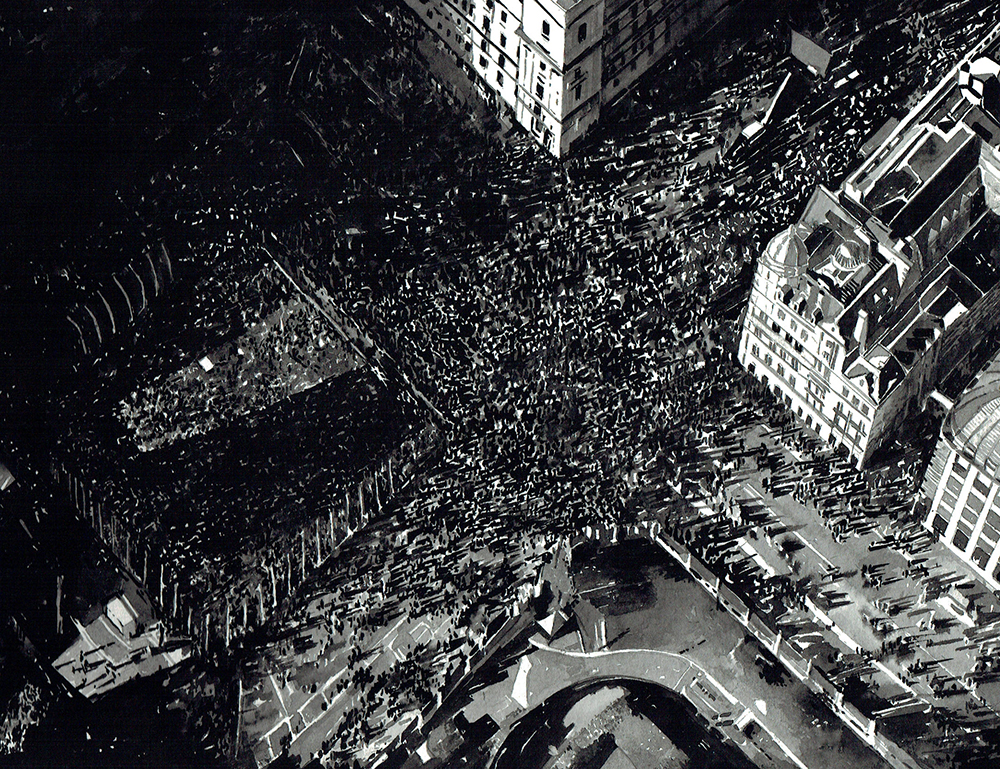

/Painting by Jase Falk.

By Jase Falk:

Warm light and wanting circle in through my earbuds. Patterned question marks and safety lights line the aisles of the plane. I’m missing you already as you write poems and drink matcha in Winnipeg. We weren’t steady in our love then and we aren’t now either, but in this distance and exchanged letters it felt like there was a growing—we wanted there to be a growing.

I stepped off the plane, my gender caught up in tangles of hair. The way you used to run fingers through the knots and listen to the slow hum of my heartbeat pulling up through veins traced down the length of my forearms taught me the meaning of safety. A latticework of language formed the shape of us. I needed shape to myself; had I no shape to myself? Years passed through me like how grandma used to whisper stories while the world slipped by, our cups of tea shimmering to its beat, leftover paska bread, eggs dully cooked, yokes a disintegration of yellow in the pan.

Float through Vancouver like a ghost; spectres of me dance down alleyways in graceless imitation of you. I’ve always envied the way linen hangs differently on your shoulders, like soil grew and wove it there. No lack of confidence in your cursive. My stumbling into coffee shops, penning words like you penned down words. My wanting you bore such resemblance to my wanting to be you. Your letters gave me form like the inside of my bones.

Flashes of red and yellow as I travel through the underpass. Loud sigh of my bicycle break’s un-oiled song. This city’s grid is not interrupted by muddy water. I kept peeking over the boardwalks on Granville Island only to see faint ripples of my face return.

Drift back from apartment on Davie street to wet lines and rainbows sliding down Commercial Drive. All is queer at night, but in the day we hide ourselves. All is poured out here, but back home I hide myself.

Night of fairy lights, soft guitars paired with words falling petal-like on the small crowd bundled up in wine stained blankets. There is a kind of softness that knows how to cut out space in a world which does not want it. I’m all broken open up in tasseled fissures. Never knew words that could work their way through such a thicket of skin. Afterwards, a woman shares her smoke with me. We talk by the fence while groups of warm bodies move aglow like candle light nearby. I hope to find identity. I don’t quite identify. Her words cluster and form hickeys above my collar. She knows but doesn’t say. I know, but don’t know how to say. I told myself I would not serve, but here I am passing wine amongst loving faces under porch lattice, vines carry their long bodies down to play on our shoulders. We are graced. We sing grace though we don’t know it. Don’t know who we’re singing to as wax spills over tablecloth, the light almost out. She would have asked for a kiss goodnight, but saw my unknowing for she had known it before. Warm arms fasten body to ground then fall away like the smell of rain carrying me into the night.

Your wanting spurts out in a phone call, alone with its uncertainty. I change my flight and leave a week early. The seat buckle tightens around my waist and the flight attendant asks “sir, would you like a drink?” I gather question marks from around my feet, tattoo them onto skin. You curl loose fingers around my shoulder and don’t know me. I grow into you—toss my questions in the messy corners of your room. Return the fullness of myself; put this body in motion. We tangle into one another, we still don’t have the right words, but brush chalk dust off and name each other till we find a stillness. Vancouver listens, patient in the distance, for anything to awake in the absence of its cedar.

***

Jase Falk is a non-binary writer who spends time in archives daydreaming of cedar trees and different futures where we have a chance. You can find them on Twitter here.