Fossil-Chained Grounds

/By R. M. Francis:

In July 2020 I took up an 18 month post as Poet in Residence for the Black Country Geological Society (BCGS). A role enabled by the University of Wolverhampton Doctoral College’s Early Research Award Scheme. Exploring the UNESCO Black Country Geopark I’ve written poems inspired by and set in these wonderful places. The poems are creative responses to the environment, considering how the geological make-up of the land impacts, connects and clashes with the overlooked cultures of the region.

The Black Country is famous for its role in the Industrial Revolution. Its industrial heritage forged unique and important communities and cultures. This, in many ways, was connected to the grounds that gave life to these cultures - the fossil and mineral rich grounds dating back to the Silurian era. One such fossil is Chain Coral; a now extinct form of colonising coral. Single cells branch off, forming helix, webs or chain patterns. This species colonised the area that was to become known as the Black Country. These fossil-chained grounds gave rise to the chainmakers, steelers and miners - the chain continues to be an important symbol of the region’s heritage, representing strong communal / cultural links. Chains run deep in the region’s cultural psyche - they run deep in the deep time soils.

These poems re-figure our relationship with the local environment; both in its surfaces and depths, the building materials and the forces that create them. This project considers these issues in an overlooked region, famed for its 'dark satanic mills', considering this in conjunction with conservation, ecology, sustainability, and new ways of experiencing place in the anthropocene.

The Mind Seemed to Grow Giddy By Looking So Far Into The Abyss of Time

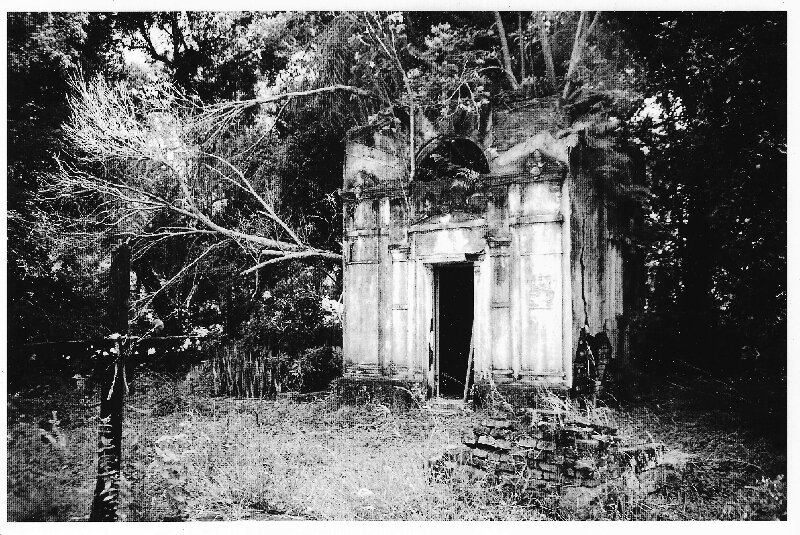

This quotation is from John Playfair's observation of James Hutton's work and echoes the sublime experience of geopoetic travel and perception. The Black Country Geopark is a group of rich, lush and mysterious places; drifting through them with a geopoetic lens has profoundly impacted my own sense of place and heightened my passion for this region's history and culture. There is something special and astonishing in the experience of getting lost and being awestruck in sites that are just outside or on the edges of our everyday realms.

Take West Park in Wolverhampton - here you'll find huge glacial erratics pitched in the park grounds like ancient totems. They travelled hundreds of miles during the glacial epoch, and are older still. A poignant reminder of the toddlerdom of humanity on Earth. You can touch this piece of ancient movements where kids play football, where dog walkers and joggers circulate, just minutes from Wolverhampton's bustle. The same can be said of Hayes Cutting; a fascinating dipping sequence tucked behind a rusted rail on the Industrial Estates of The Lye. Commuters, deliveries, school runs zip passed as it sits in almost invisibility.

There is something atavistic in these sites, or something that summons and imbues atavism. I don't mean this in any negative way; I see it as a touchstone for reconnecting with our locales, lands and the Earth in a deep time context and with the tactile knowledge that runs down to the oldest parts of our biology. Alyson Hallett recognises this in her evaluations of human cultures' relationship to stones; “Since we’ve been on this planet, as humans, we’ve paid attention to the patterns of stars and the spirits that live in stones”.[1] Kenneth White talks about this, saying: "The geopoeticist is immediately placed in the enormous".[2] Francis Ponge stated "they sink into the night of logos - until finally they find themselves at the ROOT level, where things and formulations merge".[3] George Amar thinks about the embodied knowledge of reading the land "reading is like swimming or dancing [...] eskimos can read snow and nomads desert sand".[4] These are things that we can walk through, touch, see and smell, and in that, connect us to our region and our land in ways that are both intellectual and visceral. It is, like ancient wayfinding skills, embodied and physical wisdom.

Robert Brechon discuses the relationship between cognition and feeling and between self and landscape in context to the work of Fernando Pessoa:

[...] something shatters in the vision of the landscape. The exaltation of color, light and night turns against itself and falls back into the abyss of self-awareness. Intelligence takes over from emotion, which it unmasked after having caught it in the act of posing and imposture. All the symbols that the landscape suggests to the mind of the walker, far from filling it, complete the disenchantment. He can neither absorb the landscape nor let himself be absorbed by it. His conscience overflows the landscape on all sides, as the landscape overflows from his consciousness. There is no possible identification or consubstantiality between the mind and the world.[5]

It seems Totem is exactly the right word for West Park's erratics, and I'd use it for the geological cuttings and other features across the region too: that which, with a strange sense of animism, calls and connects people and place.

***

Errare

They know their address, they don’t know where they are.

Kenneth White

West Park wanderer,

erratic and stiff,

exforms in shades

cast over pathways:

Eros pole, glacially

guided from Arenig -

an arrow rebinding space.

Fred and Ken err perma-trias

tracks, check the state of chestnuts

and their own scape. Iss too icy still,

ay it, me mon. Them ay ripe. Shrug.

On to bowling green

and their own Aegil,

but never without a slight

palm pat against wet Felsite -

cosmos-pointing and terrafirmed,

enforming in firm attention -

a honing farewell.

***

Thursday: Beacon Hill Quarry

Our Roy said iss scarred -

beautymarked by beacon fires,

Wrottersley’s luna scopings.

He shepherds limestone ways,

lighting lens on knapweed, carline

ox-tongue, heeding optic glares

against hairstreak flutterings.

Roy said, they’m rare, our kid,

rare beauts on beautmarked mount.

Thass why Sedgley Morrismen come

circlin’ among whitsun flames.

Yo’ cor ave a beacon wi’out watchmen.

He lays the ley’s spine, supporting

steep steps. Sunrays make dirt glimmer,

magnifies silty mudstone and brown lime,

lagoon shallowed in Gorstian days (if earth bones

know what days mean) and further to skeletal

stems of sea lily, bryophyte, velvet worm. Concestors,

hand holding, forward facing, tracing and traced in

Thunor’s forge, like me and my shepherd.

On Wolverhampton Road, we stop for fags at the BP

and sup a pint at the Mount Pleasant. He grandads me.

Reaches into pocket, hands me three black

bubbled bibbles of clinker. Tarra’abbit he says.

***

Lindworm

Lindworm under Leasowes

muddied brooke bank, tracking

tended greens and walkways;

Shenstone etched in delicate circuit

where flow, rush, plunge quilts

slow steps passed urn, bench, footbridge:

Soft drone of petrichor.

In calm it makes its goblin market,

unnoticed, unheard. Set in vermi-

oubliettes as Halesowen bypasses

flood engines on routes to Brum.

Their own flow, rush, plunge. They

used to come 'ere, but they doh come

'ere no more. Lindworm under Leasowes

leaks its mulching bites under A458, no.9,

Whittington Road and Hawne Basin ...

… turning scoop wheel under lapal tunnel

its half-sleep churning grumble-growls

in Murder Ballad rhythm out to Dudley

and the leisure steps of Leasowes’ ramblers

feel skinshedding of lindworm mercy.

***

Overhanging

Olistoliths slump-slide

as resisting stresses buckle

and atavistic avalanches - submarine,

like hangover guilt:

that dew-drenched dawn

when we grazed feet

along New Year frosts

and we didn’t speak a word

and we didn't hold hands

and we didn't see anyone

and badgers were hibernating

just like the trees - seem unstill.

Up Dolerite dyke, the Heathen Coal

underhung in extract where brittle

bramble waits dusk-strike. She says,

there's something in the extraction,

something seeding, imbedding, gulfing us.

***

R. M. Francis is a lecturer in Creative and Professional Writing at the University of Wolverhampton and author of five poetry pamphlet collections. His debut novel, Bella, was published with Wild Pressed Books and his poetry collection, Subsidence, is out with Smokestack Books. Wild Pressed Books recently published his second novel, The Wrenna and he co-edited the book Smell, Memory and Literature in the Black Country (Palgrave). He is currently the Poet in Residence for the Black Country Geological Society.

***

Notes:

[1] Hallett, A., Stone Talks (Axminster: Triarchy Press, 2019) p. 13

[2] White, K., ‘The Great Field of Geopoetics’ from The International Institute of Geopoetics: Founding Texts, https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/fr/textes-fondateurs/8-le-grand-champ-de-la-geopoetique

[3] Amar, G., ‘The Meaning of the Earth’ from The International Institute of Geopoetics:Geopoetic Notebooks, https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/fr/cahiers-de-geopoetique/24-le-sens-de-la-terre

[4] Amar, G., ‘From Surrealism to Geopoetics’ from The International Institute of Geopoetics: Geopoetic Notebooks, https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/fr/cahiers-de-geopoetique/118-du-surrealisme-a-la-geopoetique

[5] Brechon, R., ‘Landscapes by Fernando Pessoa’ from The International Institute of Geopoetics: Geopoetic Notebooks, https://www.institut-geopoetique.org/fr/cahiers-de-geopoetique/28-paysages-de-fernando-pessoa