Ghosts

/Photo: Lukas Becker

By Emily Richards:

4th November 2013

Glasses clink. A black dog flits by my feet into shadows. On the island, there’s no light tonight but stars. Yet in the castle, it’s a summer evening. The ballroom is lit up, just at the edge of my gaze. The dead stags have wary, wild brown eyes. They look at me as I move quietly through dark rooms, wandering time’s corridor to the days where they were alive and running, out on the rainy hills; and where a maid, her face veiled in the past, carries trays from drawing room to kitchen, past the billiard room. Sounds of laughter echo behind her, words just out of range. I wonder what stories would be told if I could hear the words clearly, not just the echoes. If I could be the ghost inside their house.

*

I am walking down a narrow corridor. Tall cupboards line the walls, so close that I sometimes have to turn sideways as I pass. A green emergency light burns steadily against the darkness in its little box, and the carpet hushes any sound but that of my own breathing. I can feel the weight of the castle pressing against the flaking, yellowed ceiling above me, the heavily papered walls closing in like a blanket wrapping me in the familiar smell of old wood, old mould, old paint and that unnameable scent unique to this very particular place.

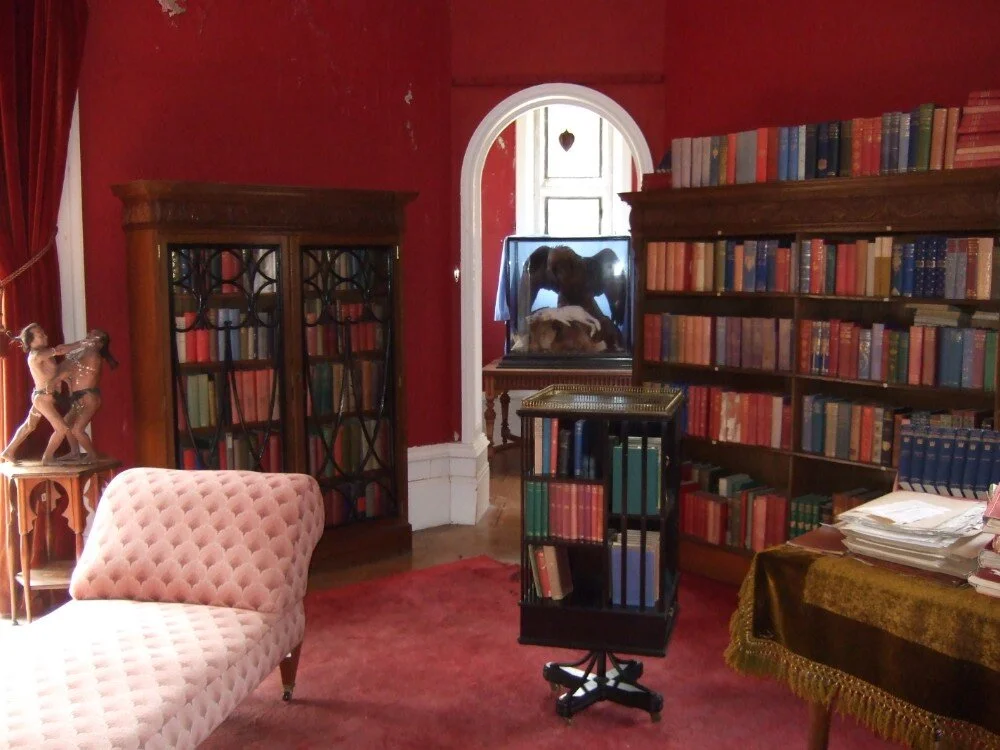

Coming up on my right, there’s a darker space: the open door to the empty ballroom. If I were to step through it, I’d just be able to make out the fading silver stars painted on the high blue ceiling; it’s only three o’clock in the afternoon, but here on the Isle of Rum in the north of Scotland, it’s already too dark for any light to make its way through the stained glass windows. And even if the days were longer, you’d still see nothing but the sky. When the castle was built, the windows were placed so that no-one could see in. Monica and George would have danced here; servants would have stood at the hatch in the corner to pour champagne or, for Monica, lemonade. The rumours say all sorts of things about Lady Monica Bullough, George Bullough’s wife, but they don’t tell you that she was a teetotaller; there’s a lot they don’t tell you. Up in the gallery, moth-eaten curtains cover another space, where the tiny orchestra from George’s yacht, the Rhouma, played Strauss or swing-time. There is a sprung floor, so that you can dance more easily, and I know already, just two months into my life in the castle, that when I step onto it, it will creak.

I am not afraid, exactly.

Low to the ground, a golden, fishy eye looms up suddenly; the stuffed tarpon, or half of it at least, hangs in its glass cabinet, its silvery scales glittering in the shadows, its gaze turned always to the left. There it hangs, motionless in its imaginary Caribbean sea; perhaps this was the one that Monica caught. In the photograph, she stands triumphant, barefooted on the wooden deck of the Rhouma, her Edwardian dress hitched up to her knees, a bearded sailor helping her to winch the fish up from the sea.

I’ve reached a little hallway, at the bottom of the back stairs; a place nearly at the end of the castle, where another emergency light illuminates George and Monica’s relief map of the Isle of Rum: brown lumpy mountains, green moorlands, a child’s blue sea. White painted writing labels Kinloch Castle, their summertime home, at the head of the bay after which it is named. To my left, cold rain is hammering on the glass door where really, the castle ought to end. But just ahead of me, there is instead another doorway, its frame drooping, and then another, half-blocked by a heavy black pedestal and its door jammed at an odd angle. I make my way carefully across the gaps in the floorboards, squeezing past the pedestal, and manoeuvring my way around this final door. And now finally, I’m here. Inside the library. Now I can settle into the sagging chair where the pile of the velvet has been rubbed away over the past hundred years or so, and tell a story. Are we sitting comfortably? Then we can begin.

Photo: Lukas Becker

But can we?

Alone in George and Monica’s library, where even the sound of the rain is hushed, I’m suddenly aware that I have set out to tell their story, but I’m thinking about my own. I came here to join my wife because she’d found a job here, looking after the castle. But I’m not sure what I’m doing here. Nor is anyone else. They’re not sure, really, what I’m for. With just over forty people living on this island, the question matters.

There are still not enough houses to go round, no roads, one shop, a few ferries a week in winter if you’re lucky, when the storms allow for them to arrive at all. Though it’s only seventeen miles away, the mainland, with its huge extended families, cosy knitting circles, West Highland Railway, Highland dancing competitions and tourists, has become a remote world; a world of communities, names, signs, directions, possibilities.

Here, although it’s officially still a few hours to sunset, the library’s already full of shadows. The sun doesn’t get above the mountains in winter, and winter comes early to Rum. The stuffed eagle, raising victorious wings, and his victim, the white hare, are just outlines against the turret window; when you come in you get a shock, wondering what they are. Here, dimly, is the faded chaise-longue in the middle of the room; here the chipped clay warriors eternally wrestling each other; and an alarming portrait of John Bullough, George’s millionaire, patriarchal papa, said to have been kind to his workers but cruel to his wife; John Bullough who is buried alongside George and Monica on the other side of the island at Harris; John Bullough whose remaindered Speeches, Letters and Poems fill the spaces behind George and Monica’s books in the library in their dozens. He’s everywhere; but he never saw the castle.

Kinloch Castle was George Bullough’s dream (‘a dream in stone, glass and gadgets’, as Alistair Scott has put it), built from 1897 to 1901 after George inherited the island and, at the age of just 21, become one of the wealthiest men in Great Britain, though his grandfather had come from the Lancashire slums. His family’s story was a rags-to-riches fairy-tale, with a darkness never far from the surface; and like a fairy-tale castle, Kinloch Castle stands at the edge of the sea, seeming to warn off invaders. Or perhaps it’s inviting them in for a party? Built of pink Arran sandstone at George’s special request, the castle is not only a dream but a fantasy, constructed not to give battle, but to house stories.

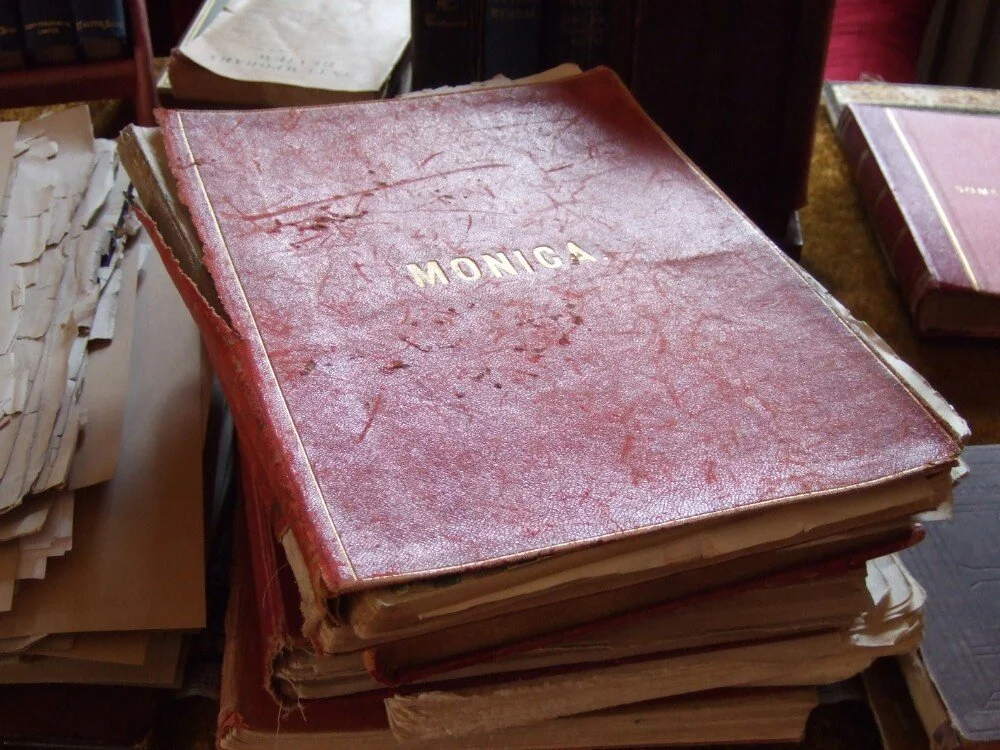

And so it did. The Great Hall proudly displays a giant bronze eagle – said to be a gift to George from the Emperor of Japan – together with photographs, lion skins and ivories from Africa, knives from Borneo and shells from Madagascar from the world tour George undertook in the 1890s. In the mahogany-lined dining room, another, darker story unfolds; the unsmiling portraits of George’s father, grandfather and grandmother stare across the room at a portrait of George himself, vulnerable at fourteen, hinting at the poverty and violence that haunted the family’s life. Beautiful, adventurous Monica, born Monique Ducarel, whom George married in 1903, filled the castle with her own story of who she could have been if her family had not been exiled from France in the Revolution: pictures of Napoleon (rumoured to be a distant cousin), delicate Sèvres china, books about the Empress Josephine. Together, the Bulloughs introduced hummingbirds, miniature alligators, a Japanese garden; telling a story of pleasure, as if to defy Rum’s inhospitable, stormy coast and their own pasts.

The hummingbirds and alligators are long gone, the garden is a wilderness. Yet I still share my space with these stories. They press against me when the room is quiet, bright dots at the edge of my consciousness. Like ghosts, you might think. But not in the sense that people mean when they say, ‘Is the castle haunted?’

Places, like human bodies, age and have histories. We form bonds of love with them, as we do with people. But while we live in them or visit them, we’re usually too caught up in our own story to pay proper attention. Yet when we come to tell that story, later on, we find that the place has taken on a life of its own, and we’re just another story in its history.

*

In the winter of 2013 and for two years thereafter, the place I lived was Kinloch Castle. My own story at the time was undergoing huge shifts, even disasters, and I filled my diary with the sense of utter alienation I felt on the island. But when I tell the story now, it’s the castle and its owners, George and Monica Bullough, and the people who worked for them, that I talk about. At first, they seemed more real to me than any of the living people on the island; more real than myself. Like friendly ghosts, they folded me into a community that I desperately needed – the community of a shared place.

Photo: Lukas Becker

That same winter that I first came to Rum, an island baby was born: the first for many years. From the castle, I watched as the helicopter descended in sheets of rain and a tornado of noise, wind slamming the trees, to take the expectant mother off to Inverness. And in the days that followed, where we didn’t know if the baby had been born safely or not, I realised that I didn’t want to be a ghost. I wanted to do something, however small, to play my part on the island. There was just one thing I was qualified to do; and at that very particular time, I was the only person who could do it. I could tell the story of the castle, and make those voices, that I could so nearly but not quite hear, audible again. I could link the past to the present, help create the community I longed for.

It’s only recently that I realised my story about the castle is also my story about myself. More importantly, it’s a story that lets other stories be heard: of the factors, visitors, contractors, teachers, castle staff and gardeners who came to live or work on Rum over the years; of delayed deer sent by train from Kings Cross to the island in the 1920s; or, for example, the story of John Stewart and Catherine Murray. One day in 2015, a middle-aged French woman arrived on the island to show us a photograph of this beautiful couple, her grandparents, who had worked as footman and housemaid in the castle before their marriage. The image shows them on a day out with their colleagues; there they sit, smiling yet serious, by the burn that rushes down from the mountains in the winter. It is a romantic picture, in a sense; but it also tells a story of the future. At George’s wish, the power of the burn was harnessed to provide electricity, just as it still does today, over one hundred years later; it was one of the many technological inventions and innovations George brought to the island.

And while George looked forward, imagining the future, I look back to the past, trying to imagine his and Monica’s lives on this island, at that time. In this space where our imaginations move backwards and forwards, in the underground roots of our different stories communicating with each other, past and present meet. Not as ghosts, but still, as a kind of haunting; a kind of community.

***

Emily Richards is a writer and translator who grew up in Canterbury, UK before moving to Berlin in 1992 to discover her German roots. Since then, she has also lived in Yorkshire, London, Lyon and the Isle of Rum in Scotland, where she began to write seriously about the impact of places on our narratives. She is currently completing her memoir about the Isle of Rum, The Castle Captured Me, which was shortlisted last year for the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize