Five Questions for... Jessica J. Lee

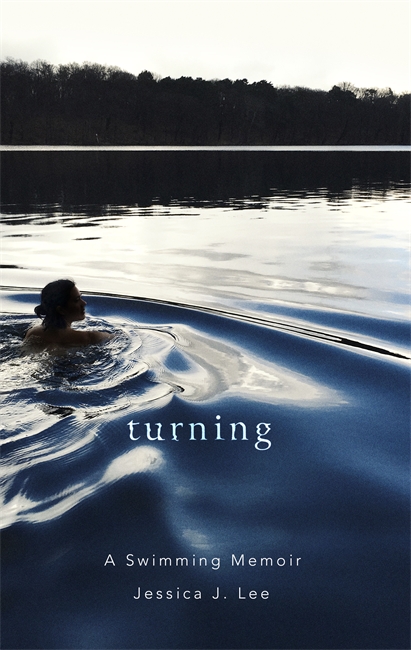

/Two years ago we reviewed Turning, her memoir about swimming in the lakes around Berlin. This autumn Jessica J. Lee is back with the autobiographical Two Trees Make a Forest: On Memory, Migration and Taiwan. She is an environmental historian, writing tutor, nature writer and editor of The Willowherb Review, an online platform for nature writing by writers of colour. Jessica writes with the precision of a botanist but without the pretence that nature writing has no singularity, discarding the old cliché haunting the genre: that we all experience the environment in the same way, that diversity doesn’t matter and doesn’t exist.

What does home mean to you?

Multiplicity. It’s taken me a really long time to realise that home didn’t have to be singular, that I didn’t need to pick one place to call home. Both my parents are immigrants, and I’ve been an immigrant myself: instead of seeing that as a kind of “dislocation”, I’ve made a conscious choice to see that as productive, as a way of saying I belong to many places. I was born in London, Ontario, which people seem to find confusing because I lived in London, England for so long. Halifax (in Nova Scotia). Toronto. Berlin. Taipei.

Which place do you have a special connection to?

I wrote my PhD dissertation about Hampstead Heath, which I lived next to through my early twenties. There was a beautiful lime tree that I used to hang out under, reading, resting, dreaming, crying: it bore witness to a lot of my most transformative moments in young adulthood. The tree came down in a storm in 2012, but the spot where it stood still draws me in. I have its leaf tattooed on my arm.

So I’d say there, but also: the bay at my family’s cottage in Canada, the cafe window in Berlin where I usually sit and write, the Taiwanese breakfast shop in Taipei where I get cold soy milk and hot shaobing youtiao.

What is beyond your front door?

My street has one of the most beautiful views in Berlin, I think: it’s abnormally long and tree-lined and lovely. To the left, you’ll find more children and ice cream shops and wine bars and pet stores than necessary, and to the right you’ll find a busy road with a tram that races back and forth over the old Berlin Wall border all day. There’s a spicy hand-pulled noodle shop not far away, which is probably the best thing within walking distance.

What place would you most like to visit?

This is an impossible choice! There are so many countries I’ve yet to visit—Japan, Norway, New Zealand—but if I can be really specific, I’ll say Jiaming Lake in the Central Mountains of Taiwan. It’s a teardrop of a lake at the top of the mountains, famous for being a shallow, glassy mirror of the sky. People used to say it was formed by a meteor strike, but it was actually formed by glacial movement. But it’s a nightmare to hike to because of permits, the logistics of getting to the trailhead, the three-day trek, etc. I’ve twice had journeys to the Jiaming cancelled, so it’s become something of an obsession for me to one day actually make it there.

What are you reading / watching / listening to / looking at right now?

I have the bad habit of reading many books at once. Currently, Brandon Shimoda’s The Grave on the Wall and Yoko Tawada’s The Last Children of Tokyo during the day, and Ben Aaronovitch’s The October Man as bedtime reading. I watch too much television—it’s one of the only ways I can switch off at home—so I’m currently finishing with Jane the Virgin. And for music, I’ve returned to Japanese Breakfast’s Soft Sounds from Another Planet on repeat.

Jessica on Twitter

Website

The Willowherb Review