Strange City: Thomas Willson and the Primrose Hill Pyramid

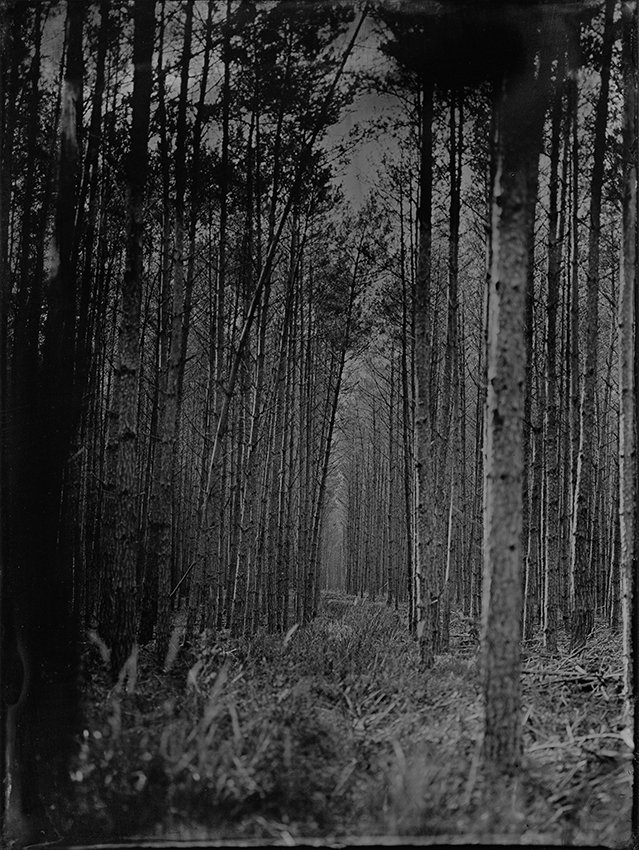

/Artwork: Laura Haines

By Dan Carney:

In the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, increased migration into London and rising fertility rates caused the city’s population to almost double, from 750,000 in 1760 to 1.4m by 1815. Burial space was at a premium. London’s graveyards, generally centuries old, were already foul smelling and disease-ridden, overpopulated and unfit for purpose. Bodies were buried on top of others, with older corpses sometimes even exhumed, then scattered, in order to make space for fresh ones. By the 1820s, with the widespread implementation of cremation still several decades away, it was clear that the problem had grown too pressing to ignore. A lively public discussion was underway regarding the reformation of interment practices.

A popular idea was the building of large out-of-town garden-style cemeteries - something first considered over one hundred years earlier by Christopher Wren - but architect Thomas Willson suggested an alternative solution. Inspired by the craze for ancient Egypt that was sweeping Europe, Willson proposed the construction of a vast pyramid mausoleum atop Primrose Hill. With a 40-acre base as large as Russell Square and a height of 1500 feet (four times the height of St. Paul’s), the 94-storey, granite-faced structure would contain 215,219 storage vaults, arranged honeycomb-like along concentric corridors, accessed via ramps and hydraulically powered lifts. There would be capacity for five million bodies, as many as could be interred in a more conventional 1000-acre “horizontal” cemetery. At the summit would be an astronomical observatory.

Willson first exhibited his idea at the Kings Mews exhibition space at Charing Cross in 1828 before publishing the plans in full two years later. He described his pyramid as a “coup d’oeil of sepulchral significance unequalled in this world”. It would “teach the living to die, and the dying to live forever”, and be the centerpiece of an ornamental site, where families coming to pay their respects to loved ones could picnic on the grass outside. It would also offer investors the chance to make a killing - freehold vaults would cost between £100 and £500, depending on size and location, with further income generated by leasing additional vaults to parishes. Willson estimated that, once filled - at a rate of around 40,000 burials annually for 125 years - his structure would bring in a profit of almost £8.2m. He set up the Pyramid General Cemetery Company in order to promote the project to interested parties.

Reactions to Willson’s ideas were mixed. The London Literary Gazette was unequivocally hostile, writing: “This monstrous piece of folly, the object of which is to have generations rotting in one vast pyramid of death… is perhaps the most ridiculous of the schemes broached in our scheming age.” One prominent figure in the burial reform movement, John Claudius Loudon, was impressed with the capacity but also had reservations. Writing in the Morning Advertiser, Loudon feared the expulsion of foul-smelling gasses – “mephitic exhalations” - and was also perturbed by the idea of bodies being buried away from the earth, in “…any way which prevents the body from speedily returning to its primitive elements, and becoming useful by entering into new combinations – vegetable, mineral, or even animal, in aquatic burial.”

Willson’s plans went as far as being presented to parliament in 1830, but interest ultimately petered out, with planners and architects favouring the idea of garden cemeteries. Willson, however, persisted, resurfacing over two decades later at the Great Exhibition in Crystal Palace in 1851 with a model of a “Great Victoria Pyramid” mausoleum, earmarked for Woking Common but similar to his previous plan in most other ways. The project received favourable press coverage and another attempt was made to find investors, but interest again waned. Willson’s last sepulchral pyramid-related activity appears to have been in 1853, when he was accused of defrauding a young man called James Sykes, who had offered a £200 inducement loan to anyone offering him employment. Willson hired Sykes in the office of a “British Pyramid National Necropolis Company”, and had received the money, but had fired him several months later with no sign of repayment. Willson died in 1866, but his idea endured, at least in his own family. His son Thomas, also an architect, submitted a plan in 1882 for a pyramidal mausoleum to house the body of the recently assassinated US President James Garfield. Garfield’s widow was, however, unimpressed, and chose another design for her husband’s final resting place.

Although the likes of Kensal Rise, Highgate, and the City of London demonstrate that the garden cemetery enthusiasts won the argument, Willson’s abandoned plans offer an intriguing insight into an alternate London, one in which his pyramidal sepulchre – taller than The Shard – would be the highest building in the city (and third highest in Europe), one of its most debated and controversial structures. The designer Laura Haines offers a glimpse into this parallel world in her 2016 project Metropolitan Sepulchre, envisaging the vast structure amidst the Blitz, then surviving as a tourist attraction, dominating the modern skyline.

The Egyptian theme may have been a voguish peculiarity of the era, but with burial space running out in cities all over the world, particularly those high in populations for whom cremation is taboo, the idea of vertical burial structures in London – or its vicinity - may one day resurface. Some boroughs are now completely out of space and are “recycling” existing plots, back to burying fresh bodies on top of old. Vertical burial methods have been used in other cities for a while. The world’s tallest cemetery, the Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica in Santos, Brazil, opened in 1983 and hosts around 16,000 burial units over 14 storeys. Current extension plans will see it rise when complete to 32 storeys, with space for 25,000 units. Echoing Willson’s vision of his pyramid as part leisure destination, the building also features a tropical garden, with turtles and a waterfall, as well as a classic car museum.

In Petah Tikva, Israel, a 22-metre high structure at the Yarkon cemetery offers space for 250,000 bodies, with Judaism’s requirement that bodies be buried in earth cleverly fulfilled by dirt-filled pipes inside the building’s columns, technically connecting each layer to the ground. The six-storey Kouanji Buddhist temple in Tokyo requires mourners to use swipe cards to have their loved ones’ remains delivered to them via a conveyor belt system. Ideas for vertical burial structures have also been seriously discussed in cities as diverse as Mumbai, Paris, Oslo, Mexico City, and Verona. It may be that Thomas Willson’s ideas, usually a strange footnote in articles on unrealized buildings or 19th Century Egyptian Revival architecture, were simply slightly ahead of their time.

***

Dan Carney is a writer, musician, and lecturer from northeast London. He has released two albums as Astronauts via the Lo Recordings label, and also works as a composer/producer of music for TV and film. His work has been heard on a range of television networks, including BBC, ITV, Channel 4, HBO, Sky, and Discovery. He has also worked as an academic psychology researcher, and has authored articles on subjects such as cognitive processing in genetic syndromes and special skills in autism. His other interests include walking, hanging around in cafes, and spending far too much time thinking about Tottenham Hotspur.